Last week I joined the other members of the Web Science Trust at the 75th Anniversary of the Turing Test at the Royal Society London.

A link to the full recording of the event can be found here - Turing 75th.

As with the 50th Anniversary of the Internet held last year the day was a wonderful opportunity to hear from so many real experts in the field of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence who have deep knowledge and experience over many years, especially at the minute amidst so much AI hype.

The day was anchored by Professor Dame Wendy Hall in her inimitable style making everyone feel very welcome and providing the personal touch throughout with her own stories.

What was fascinating from the outset was the various interpretations of Turing's famous test (or tests, apparently there are 8 Imitation Games according to Professor Sarah Dillon).

Did Turing posed them as a joke? Were they intended to test 'intelligence' or deception? Do they reveal anything about how the human mind actually works?

Alan Kay, one of my absolute heroes since my days visiting Xerox PARC, and one of the 'fathers' of the personal computer, kicked things off with his keynote describing how Alan Turing hated the theatre because it was all about deception - what is 'real' and what exists only in the mind?

What Fools These Mortals Be! (Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act 3, Scene 2)

Opening the day with this bold assertion and grounding 'artificial intelligence' in both neuroscience and psychology demonstrated Kay's profound understanding of the both the science of the human mind and the impact that our smart machines are having on how they mediate how we see the world.

I think of civilization as being a set of processes trying to invent things that mediate, deflect, turn away, and modify most of the things that are wrong with our brain. (Alan Kay Pioneers, September 2021)

Kay's pioneering work led to Personal Computing (the Dynabook) and the concept of the Graphical User Interface (GUI) which we use everyday as we engage with Cyberspace. But what is the true nature of this engagement? Is it 'real' or perhaps a dream?

We are such stuff as dreams are made on, and our little life is rounded with a sleep. (Prospero in The Tempest, Act 4, Scene 1)

In considering the question of Turing's Test (cited in Computing Machinery and Intelligence 1950) what we are talking about a measure of deception, not necessarily intelligence. It is the ability of a machine to deceive the human rather than in any way a measure of the 'intelligence' of the machine. Here Kay invokes the scientific method and philosophies of Francis Bacon and his New Atlantis which inspired the Royal Society - an idealized vision of a society that embodies enlightenment principles and the pursuit of scientific knowledge.

In an age when scientific fraud is happening at scale the need for this seems to be greater than ever and the Royal Society's motto:

Nullius in verba - take nobody's word for it. (Royal Society Motto, adopted 1662)

This is the basis of critical thinking and Socratic questioning but the problem is that the hype is driving the conversation, not the scientific rigour. Whilst the machines are becoming increasingly sophisticated and 'intelligent' they are being let loose on society with minimal oversight or duty of care ignoring the advice of Butler Lampson:

Start the machines in bottles and keep them there. (Butler Lampson, PARC)

Kay's key message was that there is a fragility about the human grip on reality therefore those who play in interstice between the 'real' and 'imagined' must be held to account in just the same way as those who build for the physical world with acknowledged rules and professional standards of conduct, both of which are sadly lacking.

The second keynote was given by Gary Marcus, after an introduction by Peter Gabriel (which Wendy got very excited about!).

Marcus' own post about the event is here.

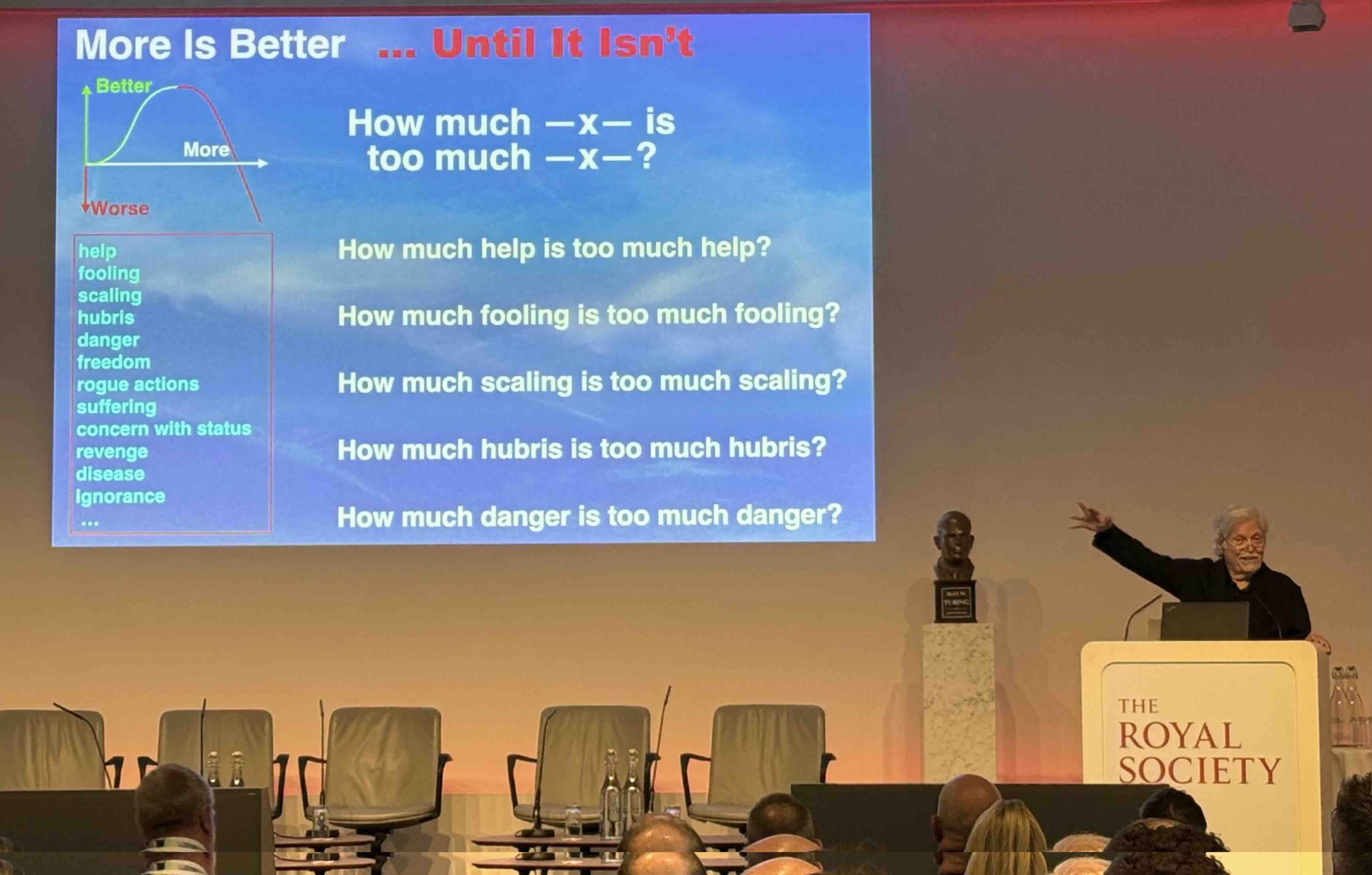

From the outset Marcus made it clear his skepticism of the current direction of AI development, particularly through scaling, which might help pattern recognition but not other problems which can't solved through brute force.

Most of all Marcus posited the question of how human society responds when we have ‘machines that think’.

Imitation is not actually the essence of intelligence

Marcus argued that the focus on scaling was in pursuit of just one solution to the quest for 'artificial intelligence' ignoring the reality that the human mind works in numerous ways (The Modularity of Mind, Jerry Fodor) with different thinking systems (Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman). Marcus sees Large Language Models as akin to System 1 whereas Classical Symbolic AI is more akin to System 2 - and to achieve 'intelligence' both need to work together. For this he suggested Neurosymbolic AI.

Underlying much of this is what Marcus referred to as the ‘tribal politics’ of the AI community, typical human group dynamics. Seen through this lens it is easy to understand how the Tech Bros are been seen as Gods (Bion's Basic Assumption of Dependency where 'the group' is deferring to leaders in order to avoid having to deal with the real issues themselves). I also thought back to the early politics surrounding the Macy and Dartmouth Conferences and the aversion to the ideas of Norbert Wiener’s Cybernetics.

The second Panel was a mixture of perspectives. Kaitlyn Regehr stressed a focus on the need for Digital Literacy asking how much of our developmental thinking was being outsourced to the AIs and what the impact is on the development of younger minds, ,particularly as so many parents are ‘digitally illiterate’. This made me think of my own reaction to Netflix's ‘Adolescence’ and the key challenges facing parents in the digital age. As one solution Regehr asked ‘how do we create an AI gym?’. I don't think this is particularly difficult having already developed our Digital Gymmasia during the Pandemic, but it is the call to action that is needed in people realising their own need to develop not just Algorithmic Literacy but a complete Digital Fluency as part of preparing for the Age of AI.

The Panel asked how to educate politicians (sigh!) with the very apt comment that

Policy follows the public will

Sadly Politicians don’t listen to scientists, they listen to the public, and at the minute whilst there seems to be moderate trust in science public trust in politicians and the democratic process is in decline. And when it comes to AI they are using it, its adoption is increasing dramatically but most people have only the basic skills.

The challenge is that most people cannot grasp the intellectual debates around it because all too often the academics make things very complicated, something I’ve seen over the past twenty years, from the Semantic Web onwards. If an idea can't be explained simply - the elevator pitch - they ignore it and will only engage and pay attention when something is REAL and staring them in the face. Most people have very limited imagination. They do not understand until something is right in front of them - holding and working with a smartphone, using an LLM, witnessing young adults commit suicide after having been advised to do so by ChatGPT, or actually losing their jobs … which is coming and coming rapidly (this from the US State of St Louis is worth reading).

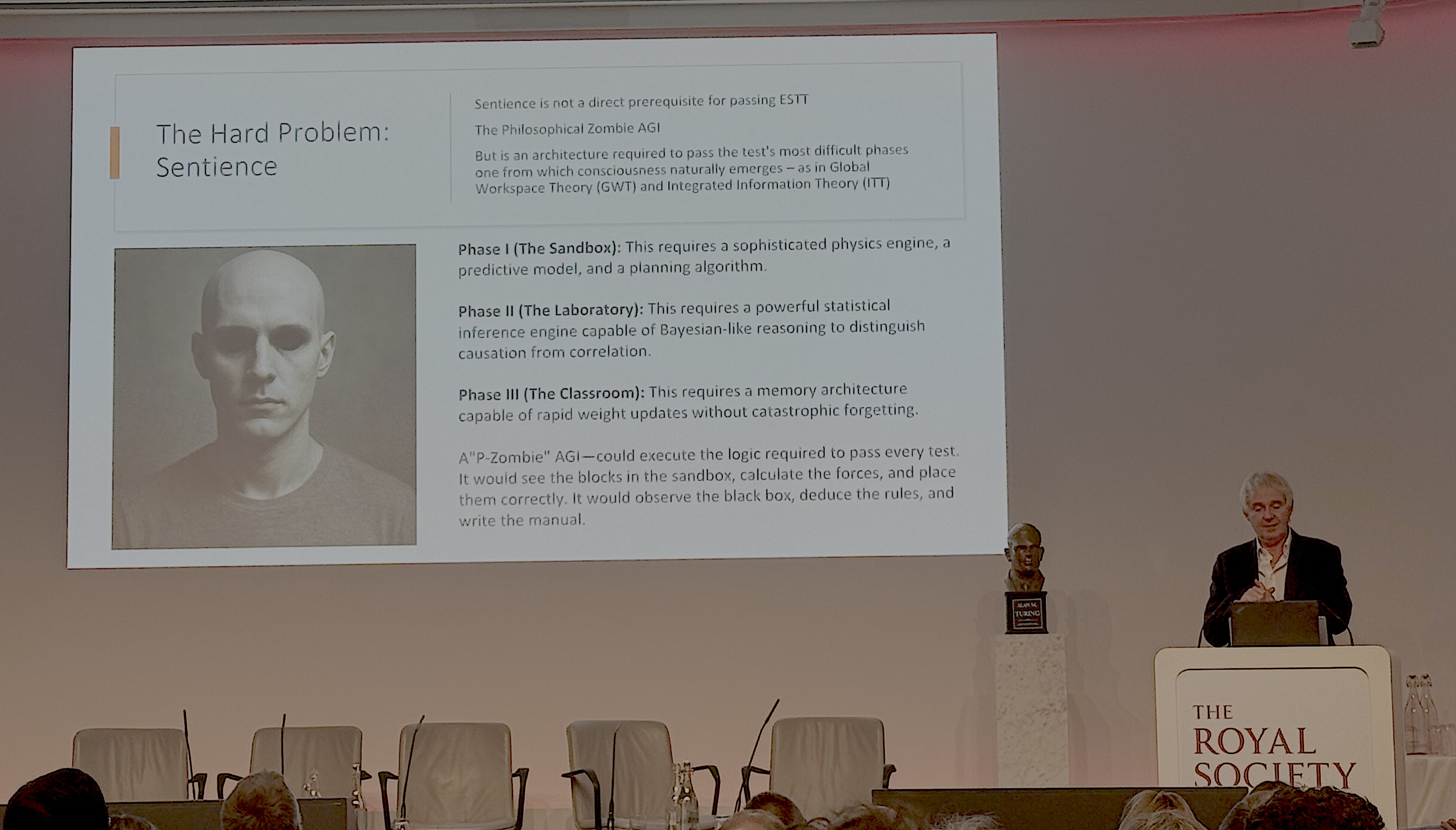

Nigel Shadbolt took us into the realm of philosophy and the concept of Zombie AGI, and intelligence that 'behaves' as if it's advanced and functional but lacks any genuine sentience or conscious experience.

And so back to Turing's Test/s and the ability to deceive the humans.

Anil Seth made it very clear that we don't want a sentient AGI and there is no predestined or preordained path for its development. However we proceed we must do so within a careful framework (for instance Jonathan Birch's Edge of Sentience) articulated through clear protocols for adoption.

Technology can make us forget what we know about life. We need to remember. (Sherry Turkle, Reclaiming Conversation)

As always these events at the Royal Society are thought provoking and intellectually inspiring but it reinforced to me a couple of things.

There seems to be a binary nature in the conversations around AI - it's either good or bad, glass half full or empty

I believe we need a much more nuanced discussion which recognises that AI, in all its forms, is one of the most powerful and significant (perhaps THE most significant if you believe Yuval Noah Harari) technologies that humanity has ever invented. It is going to profoundly change humans and the societies we live in; it will bring enormous benefits to humanity, but it also poses significant challenges and threats.

It is worth listening to people such as Emad Mostaque, Mo Gawdat and financial journalists and commentators like Jonathan Pain. These people, like so many in the academic world, see AI through the prism of their own biases and rather narrow mindsets, but it is they who are driving much of it's development and adoption.

This conversation with Jensen Huang, founder & CEO of NVIDIA, is also revealing as Huang makes a number of claims:

All of these may well be true but the more I listened to this interview the more I felt the disconnect between these people and anyone outside of the 'tech bubble', especially the tech bubble in America.

The comment that the only thing to do with a fast moving train is to get on board and figure it out once you're on it was at best naïve and at worst supremely arrogant. It is also ignorant of aeons of human history when people have decided that they simply don't want to be on the train and they want to make different choices. Where those choices have been ignored has come social unrest, revolutions and civil wars - read Jared Diamond Collapse and Luke Kemp, Goliath's Curse for a start.

Gary Marcus called out the Tech Bros who are acting like they see themselves as Gods (interviews like that with Huang demonstrate this in spades!) and it seems that both the academics and the technologists are becoming increasingly distanced from everyday people. Listening to conversations like these makes me think of the movie Elysium the lessons of which are prophetic.

I came away from the Turing@75 event last week feeling that perhaps at the core of Turing's test is the test of humility and what happens when people are captivated by hubris.

We need not only Turing's intellectual humility but a universal humility

The AI train has already left and we have been far too slow in preparing for it. But prepare we must and this is in the streets and cafes, schools and playgrounds, and through some quiet reflection about the big questions now facing us.

That preparation needs to come from the ground up driven by people who must be given a say in how they want to live their lives and not determined or dicated by a small group of people obsessed with their own enrichment or personal challenges.

The Tech Bros see AI as a problem that needs to be solved, a race that needs to be won, rather than a gift that is to be given

With all the talk about the AIs and how things are going to change our way of life the key question is not about the technologies or the markets or the politicians - it's about the humans.

What is our role in an AI driven world?

What do we want it to be?

More importantly what do we not want it to be ...

Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA: This license allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator. If you remix, adapt, or build upon the material, you must license the modified material under identical terms.

CC BY-NC-SA includes the following elements:

BY

– Credit must be given to the creator

NC

– Only noncommercial uses of the work are permitted

SA

- Adaptations must be shared under the same terms